Transforming public perceptions of VAWG

- It only happens to naïve women and the women with low self-esteem.

- It only happens to women who wear revealing clothes and have no self-respect.

- It only happens to young women and girls.

- It only happens to women who were abused in childhood.

- It only happens to poor, disadvantaged women, the uneducated and disempowered women.

- It only happens in developing countries.

- Women lie about male violence.

- Women use disclosures and reports as revenge against their exes.

- Women exaggerate how common male violence is.

- Women ask for it and want to be treated like objects by men.

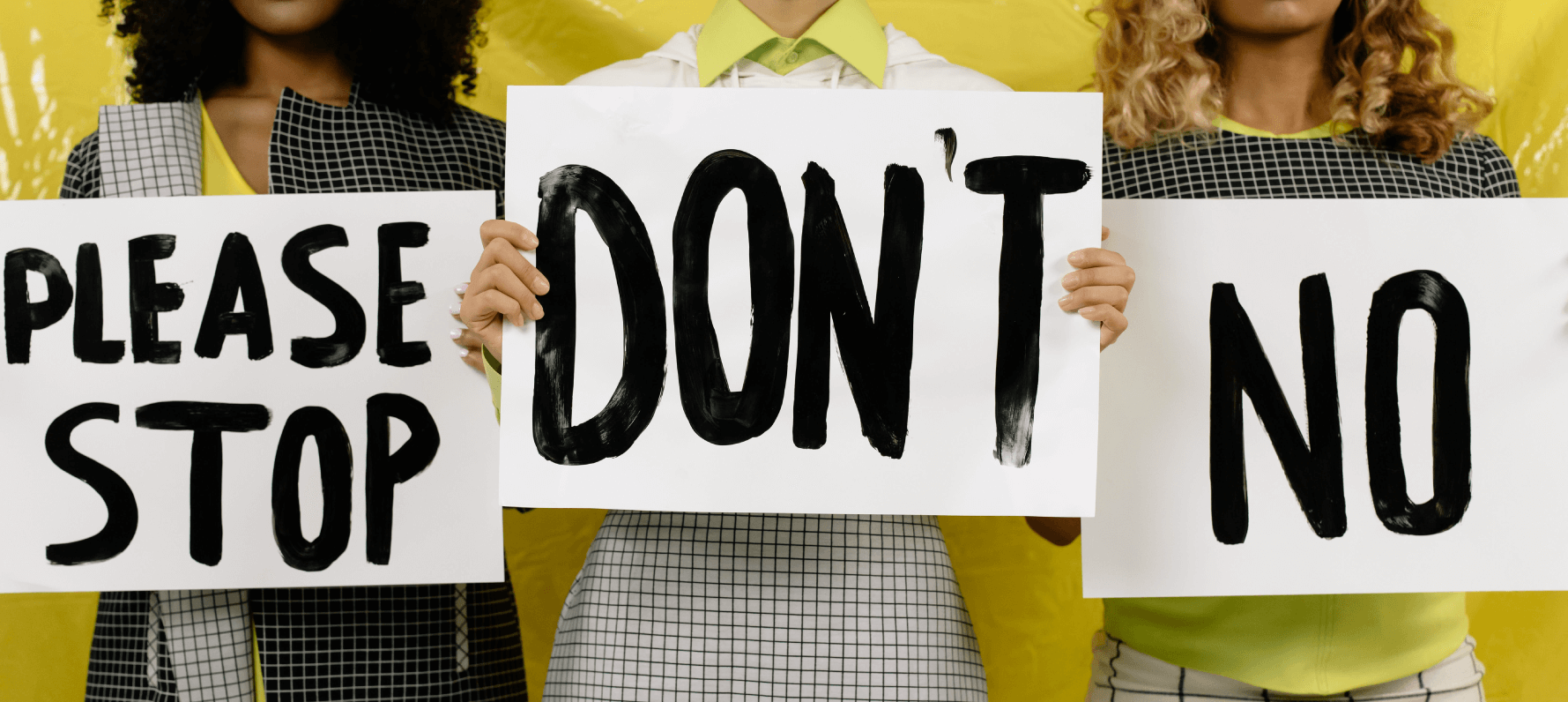

- Women say no when they really mean yes.

This list could take up my entire blog, and psychologists, feminists and activists have been trying to draw our attention to the way women and girls are perceived and portrayed since the 1960s.

The most important thing to note about all these harmful myths about women subjected to male violence is that they serve one main purpose: to erase the offender from their own crimes and decisions. Instead, the focus is switched back to the woman and everything about her comes under scrutiny. Whether it is her body shape or her sexuality, her character and behaviour is highly likely to be criticised and blamed for being subjected to male violence.

These widely embedded views impact our justice system, mental health systems, education provisions and social care services. My research on this topic showed that views which seek to blame women and girls for male violence committed against them has reached so many different levels and corners of society that we have a real problem on our hands.

Male violence against women is minimised, ignored, glorified, sexualised and excused. Women are positioned as mentally ill, liars and seductresses who lead men on, or cause them to commit acts of violence.

These views need urgent change. We need to completely transform the way we think and talk about women and girls subjected to male violence.

To that end, I want to talk to you about what I believe to be the 5 most harmful views about women and girls which need to be transformed, and I want to tell you what I have been doing for the last 11 years to try to transform these views, to varying levels of success.

The five beliefs I will discuss are:

1. The abuse, exploitation and murder of women and girls is rare;

2. Women and girls are asking for it;

3. Women and girls should take responsibility to protect themselves from male violence;

4. Women and girls exaggerate or lie about abuse and violence;

5. Women and girls are respected and supported when they disclose their experiences.

In 2014, after a long day managing a rape and domestic abuse centre, I nipped to my local shop to get some bread. The woman who always served me on the counter noticed that I looked particularly tired and troubled. She asked me if I was okay, and I responded that I had had a difficult day at work. She asked the question I often dread being asked in public, ‘What is it that you do then?’

I tried to dodge the question by saying that I managed a charity, but she probed and eventually I told her that I worked in a rape and domestic abuse centre in our town.

The woman gave me the most extraordinary look. It wasn’tsadness, or pity, or shock – it looked like confusion. She laughed. And then she said the words:

“Well! You mustn’t be very busy then, must you?”

I stared at her, thinking of the 357-strong waiting list we had for counselling and support services.

“What do you mean?” I replied.

“Well, you know, all that rape and abuse stuff, it doesn’t happen around here does it? You can’t be very busy…”

And that was when I realised she was being serious. She genuinely believed that my job must be very quiet because rape and abuse of women and girls was so rare. I nodded at her, and let her continue her shift thinking that I ran this empty, quiet, unneeded rape centre in a town where the abuse of women and girls never happens. Where me and my counsellors just sit around and play dominoes for want of something to do.

It reminded me, after several years immersed in this type of work, that there were people out there who genuinely believed that the abuse and rape of women and girls was a rare occurrence in the world.

Instead of being rare, male violence against women is actually very common.

30-50% of women have been victims of domestic violence by male partners and ex partners (CSEW, 2017) and 1 in 4 girls will be sexually abused in the UK before the age of 12 (NSPCC, 2017). 1 in 5 women will be raped or experience an attempted rape and 1 in 3 women will be subjected to physical sexual violence in her lifespan according to the CDC (2015). This week, the UN and ONS released data stating that 97% of 1000 women have been harassed.

Further, 3 women per week were killed by men in the UK in 2019, representing a 14-year high. 66% of those women were killed by their partners and exes in their own homes, with others being killed by male family members, acquaintances, and strangers (Femicide Census, 2020).

Every year, millions of women and girls are trafficked across the world for sex and estimates suggest that between 60 and 100 million women are missing from the global population due to sex-selective abortion, female infanticide and deliberate neglect of female newborn babies (Watts and Zimmerman, 2002).

In my own study which will be published this summer, we collected data about women’s experiences of male violence from 4636 women and found using a new methodology that 78% of women were sexually assaulted at least once in childhood, and 46% of all women were sexually assaulted more than 3 times. 92% of women reported that they were catcalled in the street in childhood by men.

Only 6% of the women had ever reported any crimes committed against them in childhood to the police.

In adulthood, out of 4636 women, 83% reported that they had been sexually assaulted with 52% of women reporting that they had been sexually assaulted more than 3 times.

The reality is that in studies and meta-analyses across the world, violence committed against women and girls by men is actually very common.

And what about belief that women and girls are asking for it?

Research has now spanned several decades (from as far back as the 1960s) to explore why we are so likely to believe in rape myths such as that women and girls ‘ask for it’. Back in the 1960s, around 50% of the public believed that women and girls ask to be raped by the way they act or the way they dress. But have we really made any progress?

In 2017, The Fawcett Society surveyed over 8000 people in the British public and found that 34% of women and 36% of men believed that women are always partially or totally to blame for rape. My own research found that victim blaming of women and girls depends on the way we perceive the woman or girl, and on the type of offence they were subjected to. There were certain types of offences against women and girls which caused high levels of victim blaming, for example, when it came to questions where I asked men and women about ‘asking for it’, 58% of the general public sample assigned at least some blame to the woman.

The third harmful belief that needs total transformation is that women and girls should do more to protect themselves from male violence.

This might be the one that annoys me the most, especially as entire industries have popped up to exploit this belief. Now we have anti-rape knickers, anti-rape trousers and anti-rape bras (I cannot explain to you how those work, I’ve been trying to figure it out, but I got nowhere). There are even anti-rape jewellery companies now, who have essentially designed and sold little rings with a blade that pops out in case women are attacked by men, and anti-rape necklaces with a blade that pops out, and I’m pretty sure they are illegal.

Add that to the rape self-defence classes and the rape alarms, pepper spray and relentless advice to women and girls not to use the tube, use headphones, wear their hair in a ponytail, use taxis, walk home alone, jog in the park, walk in the dark, eat, sleep or breathe without protecting themselves from male violence – and we have a real culture of placing the responsibility on women and girls instead of on male offenders.

In my own study, 80% of participants assigned blame to the women who had been subjected to male violence where I described the woman as unable to say no or trapped in a situation or assault that she could not escape.

I included offences against women which used manipulation, blackmail and intimidation. These features appear to have elicited high levels of blame from the participant group with over 75% of items resulting in high victim blaming of women. The issue appears to be about the woman’s agency and lack of power in the sexual offence, which increased the amount she was blamed; because she did not ‘assert herself’ or stop the offences, she was blamed by the participants.

The belief here presents many problems, and puts us on a pathway to individualising male violence, not into the individual offender, but into the individual woman or girl. Instead of stopping offenders from abusing, oppressing, assaulting and murdering women and girls, we are giving strong public messages that women and girls should make changes to their lives, appearances, experiences and social lives in order to avoid men who want to hurt them.

In 2017, I interviewed a woman who had been raped multiple times. She told me that she wished people talked about the rape of women in the same way they talked about terrorism. I asked her what she meant, and she told me that when women are raped, they condemn the woman, but when terrorists commit acts of violence, they condemn the terrorist.

I thought about that conversation for months. I couldn’t get it out of my head.

She was right.

When innocent women are targeted and attacked by violent offenders, we tell women ‘don’t go there, don’t do that, don’t put yourself at risk’. But when innocent people are targeted by a terrorist attack, we make clear, public statements that our lives will not change, we will not live in fear, we will not change our behaviours or characters, and that we will challenge, condemn and convict terrorist offenders. There is a clear difference.

It often makes me wonder why any woman would want to live in a world like this. A world in which male violence is seen as so acceptable and so normalised that they should have to walk down the street with their keys poking between their fingers or pretending to be on the phone to try to protect themselves from male violence.

A world in which women and girls are chatted up by men and boys, and no matter how many times she says no, it is taken as ‘yes’ or ‘maybe’. A world in which women and girls have learned that the only way to stop a man or boy harassing them is to say they have a boyfriend, because the fact that she is already owned by another male is the only thing that might protect her from another violent male.

Think about the state of that world for our women and girls. We need urgent transformation. We need urgent change.

As if we needed more bad news, what about the fourth harmful belief – that women and girls exaggerate or lie about abuse and violence committed against them?

Similar to some of the other beliefs about women and girls, the belief that they lie about being subjected to male violence is a tale as old as time. As old in fact, as The Bible.

There are several examples of women being positioned as lying about rape in The Bible, but two clear examples include a story of a woman who lies about being raped by a male servant who is then punished for crimes he never committed, as a warning to women that they will be held responsible for the harm of men who they lie about.

The second example comes from the Old Testament, which suggested that women who are raped outside of city walls should be punished for leaving the city walls, and women who are raped inside of city walls should be punished for lying about it, as the argument is that if they were truly raped inside of city walls, everyone would have heard her screaming for help and would have rescued her.

Whilst these examples come from texts that are hundreds, maybe thousands of years old, not much has really changed here in 2021.

There is still a strong belief that women lie about being raped and abused by men, with research showing that 38% of soap storylines about rape depict a woman lying about being raped (APA, 2007). The media has a huge role to play in this. Despite false rape allegations being very rare (around 2% according to Lonsway et al., 2007), the media tends to overreport on cases where there are accusations of false rape allegations and this influences the public to believe that women and girls often lie about being raped. In 1980, Burt found that half of men and women from a community sample believed that women lie about being raped and almost thirty years later, Kahlor and Morrison (2007) found that participants believed that an average of 19% of sexual assault and rape reports by women were false.

The final harmful belief that needs urgent change, is that we have made progress.

Professionals, academics and members of the public say this to me frequently. They tell me how much better it is for women and girls now, and that women and girls are believed, respected and supported when they report male violence.

I have lost count of the times I have been told, “It’s not like that anymore!” when I have been criticising our national and international responses to the abuse and oppression of women and girls.

It’s as if we decided that if we tell ourselves enough times that things are better, our practice has improved and that we’ve made huge progress, it will become true. But it isn’t becoming true at all.

Women and girls are still faced with serious barriers to justice around the world. Whether it’s the rape clause in tax credits, the police being able to mine your mobile phone data and social media accounts when you report abuse, the lowest conviction rate for rape the UK has ever seen, the messages from police telling women and girls that they should keep themselves safer or the victim blaming of little girls who have been trafficked, raped and drugged by gangs of men – where is the progress?

Research has shown that when women and girls do report their abuses and rapes to the police, over 73% of them blame themselves after being questioned (Campbell et al., 2009). When women and girls tell their families that they have been abused by men, 78% of them experience their loved ones turning against them (Reyea and Ullman, 2015). The reporting rate of rape and sexual violence reduces every year according to the Crime Survey England and Wales.

This final point brings me to what I’ve been doing for many years now, attempting to cause cultural, systemic and psychological change in our professional and public spheres.

I’m just like thousands of other women; I’ve had enough of this. I have worked in the criminal justice system, rape centres, domestic abuse support, child sexual exploitation and anti-human trafficking and these portrayals of women and girls need to be changed urgently.

My work, along with the work of many other dedicated activists, female leaders and academics have consistently and robustly challenged victim blaming, rape myths and misogyny in our social systems. But transformation isn’t easy. It is especially difficult, when people do not see the need for change, or believe that what they are doing is righteous or justified.

I have worked with organisations who blame girls for being raped, and tell me that the girls brought it on themselves, and need ‘a good shock to the system’. I have worked with police sergeants who have told me that 12 year old rape and trafficking victims are ‘easy’ and ‘slags’.

I have worked with youth hostel managers who have told me that when girls lie about their age to get social media accounts, they deserve to be raped. I have dealt with cover up after cover up.

I have challenged professionals who thought that showing videos of girls being raped to teenage girls would make them ‘protect themselves from sexual exploitation’. I have worked with police teams who tell women that it will be their fault if their rapist attacks another woman, if they do not give good evidence in court for prosecution. I have worked with professionals who believe that women who have been abused and raped should not be allowed to have their own children.

Transformation is hard work. It requires critical reflection, humility, an examination of your own biases and of the cultures and systems you exist within. It means that you have to work through your own stuff – and work out how much of it you are projecting on to others. Sometimes, it means acknowledging that you have worked or lived in a way which has harmed women and girls in profound ways, and that you need to do something to take responsibility for that.

The same is true of systems. It means that organisations, governments, authorities, charities and companies must examine their own role in the way they have portrayed and treated women and girls when they have been subjected to male violence. They must explore their own strategies, policies, staff training, measurement tools, organisational cultures and belief systems.

I have been challenging some of the most powerful structures in our country for years about this, and it causes a range of responses.

One of the first things I had to do to be able to effectively challenge is resign from my job, something I never expected to have to do. As soon as I started to challenge the wrongdoing and unethical treatment of women and girls, people came after my job and started to write to my employers. I was very lucky that my employer stood by me, but I knew from that day on, that I had to go it alone.

I figured that they couldn’t come after my job, if I was self-employed. Who would give me the P45?

With that out of the way, I could concentrate on working with willing (and unwilling) professionals and organisations to explore their practice, challenge their beliefs about women and girls and encourage them to reframe everything they do. No small ask.

To finish this blog, I want to tell you two more stories. One of them highlights how resistant we are to changing the way we think and talk about women and girls subjected to male violence, and the next shows how capable of transformation we really are, when we just take a step back and think.

In 2018, I had been working on a contract for 18 months with an authority who had approached me to retrain and rewrite their materials about the sexual abuse and exploitation of girls in the UK.

My job was to rewrite and then deliver the materials to 600 professionals who worked every day with girls who were sexually abused, trafficked and exploited. I had been doing this every month for 18 months when one of my professional students approached me.

“Have you seen the email that went around?” He sort of stumbled over his words in a lowered voice and looked over his shoulder.

I hadn’t seen an email.

“They’ve sent an email out to everyone saying to ignore your training and materials, because they are causing too much challenge.”

I was shocked. We had spent months causing serious organisational change, which had included empowering hundreds of social workers to challenge the victim blaming and abuse of girls they were working with.

“They said that too many of us were challenging decisions about the girls, and that everyone kept citing your work and your training. They have sent an email to say that we are to ignore everything we learn today, and that they are going to be stopping your training.”

He was right, and that is exactly what they did.

They never replied to my calls or emails to explain why they had chosen to stop systemic change, and to tell their professionals to ignore their new skills and knowledge. The woman I had worked closely with at the authority resigned soon after, and told me that she couldn’t continue to work there knowing what they had done.

The issue here was that the authority had not planned for the way successful systemic change causes complete cultural change – and when they had got exactly what they had asked for, they were not ready for hundreds of educated, critical thinkers making better decisions and challenging poor practice. Instead of empowering transformation, they shut it down.

By contrast, while I was writing this blog, a woman from an organisation I worked with recently called me.

She called for a catch up and as we were finishing the conversation, she rushed to add something.

“By the way, the team you worked with on their misogyny towards the girls they are working with went away from your sessions and realised that they were wrong. They apologised to all of the girls and took responsibility.”

I was gobsmacked. This team had been controlling what girls wore, and telling them that wearing vest tops, shorts or skirts was ‘asking for it’ and ‘dressing inappropriately’. I challenged them and they were not at all comfortable with needing to change. They were certainly not ready for change. One of them even made a comment that they would prefer the advice of a male academic than me.

To hear that they had not only apologised to the girls but had removed all clothing rules and empowered the girls to wear whatever they wanted, was such a sweet shock – and a reminder that transformation is possible, and it is within our reach.

So, what can we all do to cause transformation?

Be braver.

Think critically about the world around us, and why so many of our systems seek to blame women.

Acknowledge the reality of male violence against women, and talk about it.

Challenge the messages and beliefs which place responsibility on women and girls for the violence of men who harm them.

- Hold systems to account, and challenge them to be better.

- Believe women, support women and stand up for their rights.

- Transformation is possible – but more importantly, it is absolutely vital.

Get more trauma-informed content!