'Take responsibility!' The socially acceptable way to victim blame women and girls

It's not okay to victim blame

It's not okay to victim blame - but it's more than okay to force women and girls to take responsibility for their rape or sexual assault. This article examines recent evidence and possible reasons for why this is happening.

Back in my PhD in forensic psychology, in my job as an author, CEO, researcher and speaker, and in my general experience of being a woman in the world (an observant, highly critical woman at that) I am became acutely aware of a societal shift away from 'victim blame' towards 'victim responsibility' - and this is something I designed a new psychometric measure in, which was published in 2019.

When I say acutely aware, what I mean is a feeling that every time I look at the news, see an advert or campaign, hear a broadcast, teach at an event or get into a conversation - I find myself listening to people who are victim blaming whilst denouncing victim blaming.

What do I mean by this?

"I'm not saying she's to blame for being raped, but she shouldn't have got into that car."

"It's always the perpetrator's fault but if he hadn't gone on the app in the first place, none of this would have happened to him, would it?"

"She's not to blame for what happened to her, but she does need to take more responsibility for her choices that evening."

"We advise all festival goers to stay aware. Please do not get so drunk that you end up a victim of crime."

"Women need to take more responsibility. They need to know that if they dress like that, they are bound to get inappropriate comments!"

"The child needs help to make better decisions and to reduce their risk of child sexual exploitation."

"She's received 40 death threats from the perp so we have advised her to take the initiative to move out of the area and to change her number so he won't be able to continue harassing her. She refuses to move so the abuse continues."

What we have here are more intelligent, more socially acceptable and more subtle examples of victim blaming. However, whilst the principle remains the same (the shift of focus from the perp to the victim), the wording is slightly softened and changed to 'responsibility' or 'decision making'. Some of these comments actually contradict themselves by claiming to understand that the perpetrator is always to blame, but then use 'responsibility' to equally blame the victim without sounding like they are blaming the victim.

Ladies and Gentlemen, we have the rise of the socially desirable response.

This interests me so much because my research focus is victim blaming and the way women and girls learn to absorb these victim blaming messages from an early age which then leads to them blaming themselves when they experience sexual violence. I believe that as a general society, victim blaming is not reducing at all, it is merely becoming more insidious and camouflaged by adapting the language used.

People know that they shouldn't victim blame, but they still feel the need to do it, so what do they do? They adapt.

Examples of the shift from blame to responsibility:

Defendables

Anti-rape wear is the ultimate shift from blame to responsibility. The slogan of Defendables on all of their marketing materials is:

"DEFENDABLES -DON'T BE A VICTIM"

Anti-rape wear is generally marketed as underwear or other garments that are designed to lock (you're thinking chastity belt aren't you? Yeah, you're not far off) so you don't get raped. Genius, eh? All those millions of women who have been subjected to rape and sexual violence and all that was really needed was a pair of knickers that can't be tugged, unlocked, cut off or ripped!

AR Wear advise women that they can wear the knickers when they go running, travelling or on a first date. Excellent.

However, there are a few

problems with anti-rape wear.

1. To prevent rape, you would have to wear these 24/7, 365 days a year

The fact that these items are marketed for running at night, travelling alone and going on first dates just confirms that the designers and founders of these companies have no idea what they are talking about. With the large majority of rapes happening within the home of the victim and perpetrated by someone they knew well (family member, partner, friend or ex partner) - women would have to wear these for the rest of their lives in order to get protection from them.

2. These knickers completely ignore wider sexual violence acts

So you've got your anti-rape knickers on, you're safe, you're confident. You are now protected from rape. Really?

The sexual offences act 2003 defines rape as including oral sexual assault. What are we going to wear to prevent that? A Bane mask? (Sorry, Batman fans.)

But seriously, what about women being forced into sexual acts that do not require the penetration of their vagina? What about being touched? What about being coerced or threatened into taking the knickers off and unlocking them? What about being sweet-talked and groomed into not wearing them?

This garment is designed based on the myth that all rapes and sexual assaults are random acts of severe violence perpetrated in unfamiliar environments by a stranger. Every other form of sexual act is ignored. The concept of grooming, threat and charm is ignored.

3. "She should have been wearing her anti-rape knickers!"

In more direct and overt examples, victim blaming will most certainly increase if these garments ever became a serious trend. Imagine the ridiculous arguments in court, by police, from friends and family, the media, and the wider public when a woman gets raped and she wasn't wearing her trusty anti-rape underwear. It's just more pathetic excuses added to the arsenal of rape-deniers and victim-blamers everywhere.

In more subtle blaming, the focus will shift to a woman's responsibility to ensure she is prioritising her personal safety by wearing these knickers. It will be her duty to ensure she is taking adequate steps to reduce her risk of rape. Don't drink. Don't wear short skirts. Don't live one hour of your life without your anti-rape knickers on. You fool.

This is not a route we need to go down, ever. Anti-rape wear is not the answer to rape. It never has been and it never will be. Forcing women to take more precautions and more responsibility to prevent their own rape is ridiculous. What about women who have been with their partners for 12 years and then they begin to show abusive behaviours and start manipulating them, eventually leading to their partner raping or sexually assaulting them? What would be said to them? That they should have worn their anti-rape knickers for their whole relationship just on the off-chance? That she 'should have seen the signs of abuse' and bought anti-rape wear to protect herself?

The fact that a lot of money, innovation and resource has been pumped into designing prototypes of knickers that imply that the burden of responsibility to prevent rape sits with the woman feels like a massive step backwards.

Public safety campaigns aimed at potential victims

Some excellent examples below contain messages that place an incredible amount of responsibility on the victim and even her friends - to ensure she is not raped. It feels as though our government and our public services have just resigned themselves to the fact that women and girls will continue to get raped so they decided to target all of their messages and resources at women and girls rather than perpetrators. It's a sorry state of affairs that teaches women that they are responsible for their rape, if they break any of the rules in the campaigns.

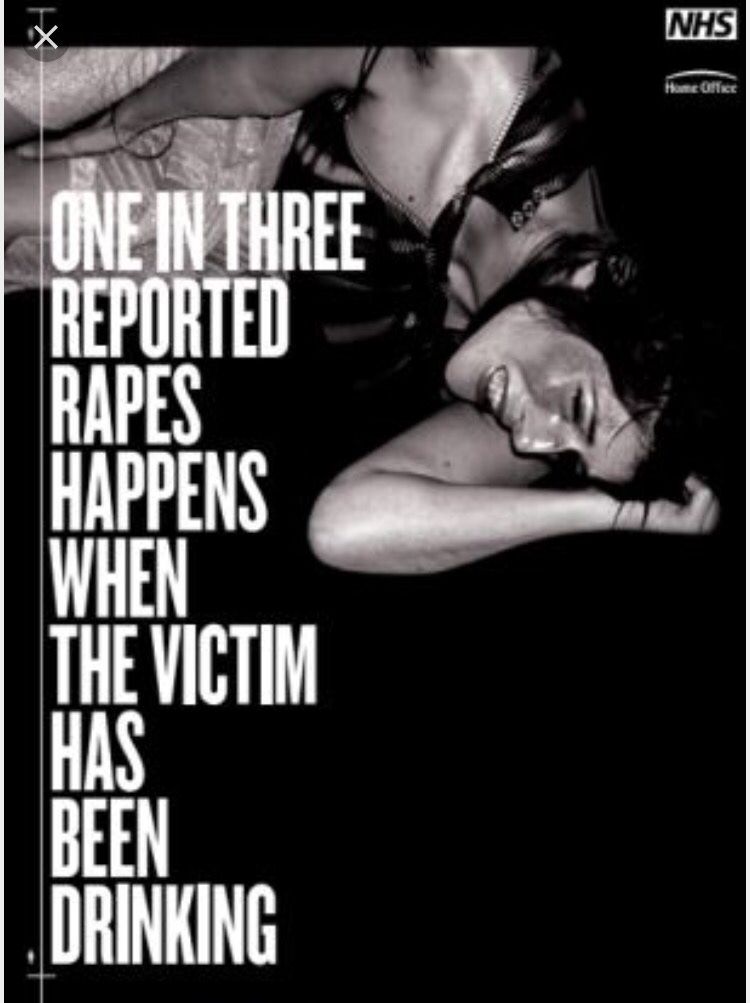

I doubt that you will be surprised to see this one. The UK and USA especially have created solid links between alcohol and rape in recent years.

Their reasoning is so frequent and confident that they make it sound as though it's the alcohol that rapes women. It's incredible really.

This poster is implying that if you drink alcohol, you might get raped. More than that, it positions your choice to have a drink over the choice of the perpetrator to target you and rape you.

This poster sends the message that if you were drunk when you got raped, you will have broken the golden rule and you will not be afforded any sympathy. Case in point: The coverage of the Brock Turner case in which the fact that the woman had been drinking was a massive focus.

You had a responsibility not to drink and you did not uphold that responsibility - you will therefore come under heavy scrutiny from both men and women about why you were drinking in the first place.

Again, another example of subtle victim blaming in which the shift is based on the responsibility for personal safety and 'looking after yourself' and 'making good decisions'.

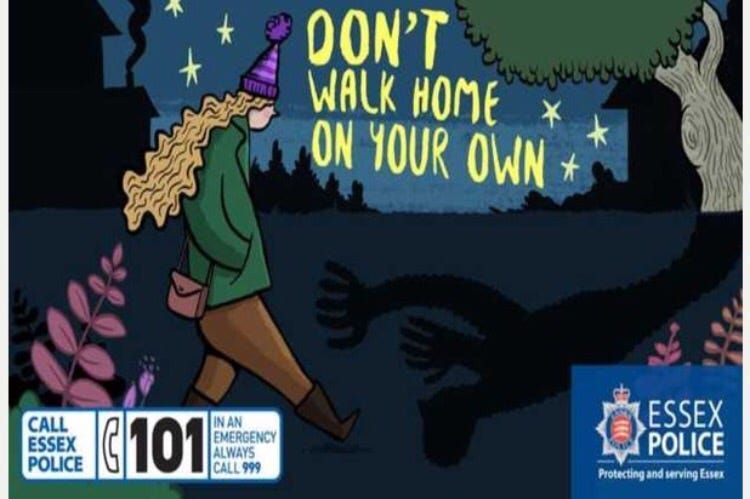

This poster by Essex Police clearly instructs women not to walk home alone. Well, what happens if they do walk home alone? Are they less deserving of justice? The answer to that, sadly, is yes. There is a high chance that people around them will question why they decided to walk home alone and why they didn't reasonably predict that they would be raped or sexually assaulted. The focus will shift back to the 'everyone is responsible for their own safety' message, which is what this poster is based on.

This is not crime prevention, this is victim blaming. However you dress it up.

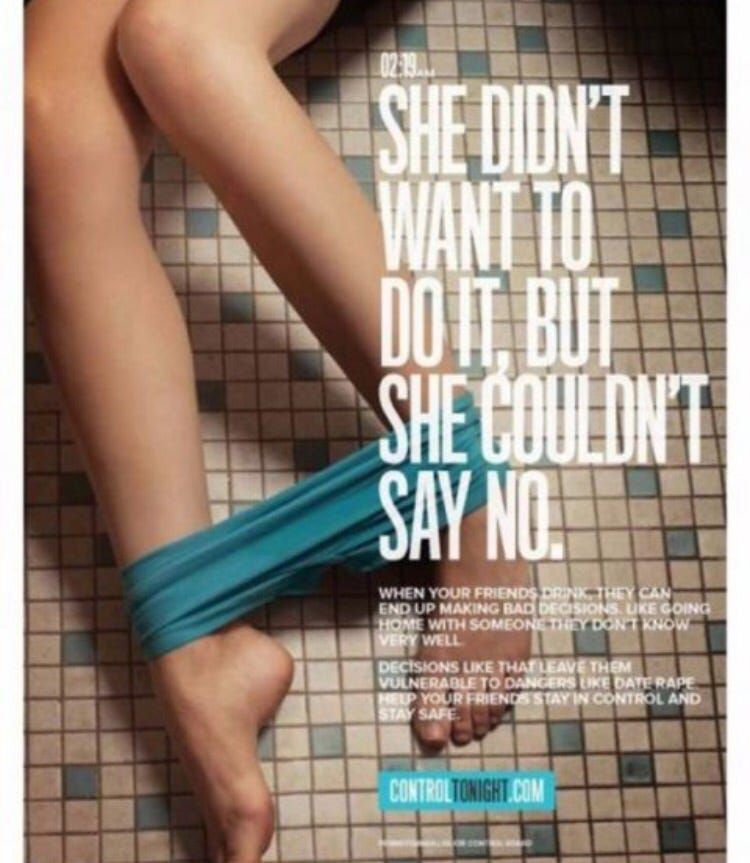

I really hate this one. The poster depicts a woman with her knickers around her ankles with a bit of text aimed at her friends saying that she might get so drunk that she will make bad decisions. However, the large text overriding the poster says 'she didn't want to, but she couldn't say no'.

Well, in my opinion, she didn't make a bad decision. Her decision was that she didn't want to have sex. However, she was unable to communicate her decision due to being drunk. And when you are too drunk to convey your decision about sex...

(Say it all together now)

That is rape.

So why exactly has this campaign reframed a very clear example of rape due to the person not having capacity to consent or communicate - as a 'bad decision' and then placed the responsibility on the friends? It's astounding.

There are hundreds of examples of these types of campaigns, resources and anti-rape wear garments and judging by the quick and critical response to most of them on social media, I would hope that a lot of these messages are being rejected - however, a critical look at academic research and professional practice in sexual violence has a slightly different story to tell. A story that ultimately suggests that the 'take responsibility' message is alive and well and unfortunately, increasing.

Academic Research

There are a string of studies into victim blaming that sparked my interest into whether victim blaming was becoming more intelligent and more subtle. Having conducted a very large literature review in victim blaming and self blame in sexual violence in 2017, which led to me designing a new measure of victim blaming, I noticed something really important that I hoped to test.

In the 1980s, Martha Burt found that around half of all people surveyed blamed women for their rape, usually using reasoning like 'they were asking for it' or 'they deserved it' or 'they brought it upon themselves by the way they were... (Insert reason here)'. As you can imagine, half is a pretty big claim. However, as someone who works in this field, I accepted that to be fairly accurate.

However, in 2005 Amnesty International performed a very large survey or victim blaming and rape myth acceptance and found that the proportion of people who blamed women for their rape had dropped to a third. Many researchers hailed this as a true reduction in victim blaming and put it down to better education, rape prevention programmes and good campaigns around sexual violence. I was sceptical.

My observations and criticisms were based around the survey items used to test people. They were so direct and so overtly sexist that I doubted whether even the most confident sexists would admit to agreeing to the items. Examples include items such as 'if a woman acts like slut, she deserves to get raped' and 'rape is a common weapon that women use against men'. I argued that it was much more likely that people were just responding in a socially desirable manner and were therefore disagreeing with the most overt examples of victim blaming and were only agreeing to the items that were more subtly worded such as the items that talked about responsibility and casual factors that 'led' to the rape. I also had issues with language and wording of a lot of items due to the scales being written some decades ago and the way the general public speak having changed.

I was delighted to find that McMahon (2010) had the exact same criticisms as I did and had done an excellent piece of research that asked university students to look at the IRMAS scale and to be honest about whether they thought people of their age group (18-25) would answer them honestly. The findings were really useful to researchers like me. They confirmed that many people would not like to be seen as agreeing to overt victim blaming but would be more likely to agree to the more subtle forms of victim blaming, which usually involve responsibility or cause rather than blame. One item about women who deserve to be raped was completely dropped from the updated version of the scale because so many participants said that even if they believed that some women deserved to be raped, they knew that it was not socially acceptable to say it like that so they would not answer that question or would lie about their views.

Once McMahon had amended the scale using updated language and the ideas from the participants, it was found that the proportion of people who blame women for their rape went back up to half. For me, this was good evidence of my argument that victim blaming was not reducing, it was evolving.

The second issue I have been looking at for many years, is language around blame, responsibility, fault and cause. In every day language, we use them interchangeably. However, when it comes to sexual violence, it appears to me that people think they mean different things. This results in people saying 'they are not to blame for being raped but they need to take more responsibility for their actions that caused it'. Most people would say 'that's still victim blaming', but in the mind of the speaker, they are reasoning that blame, responsibility and cause are different concepts that do not lead to the same level of culpability. They are saying that you could be at fault, but not to blame. They are saying that you should be held responsible, but that it wasn't your fault. They are saying that your actions caused it, but that the perpetrator is equally to blame. What!?

At the moment, other than the fact that people have started to realise that research in this area has seriously muddled up these terms, not much else has been achieved to unpick this web. I have built all of this into my PhD thesis, which you can read online, and into my first book, ‘Why Women are Blamed for Everything’ which became a bestseller in 2020. One thing is fairly clear though, 'blame' seems to carry much more negative weight than 'responsibility' which means that professional practice has already started to adopt this approach (either consciously or unconsciously) and I can see the effects.

Professional Practice Example: Child Sexual Exploitation

I am going to use a fictitious but typical case study of a child who is being sexually exploited in the UK and then unpick some of the ways the 'take responsibility' message is harming professional practice with victims of sexual violence.

- The child is 14 years old

- They have a Facebook account through which they have been groomed repeatedly

- They have been sexually exploited by a number of peers and adults

- They are taken to hotels and pubs by perpetrators in nice cars

- They are in love with their main perpetrator and have no idea why everyone thinks they are being abused

- They are being given drugs and alcohol regularly

This case would be classed as 'high risk' in the UK using the CSE risk assessment toolkits (I don't have time to go into the serious flaws in those here but the fact that a child who is already being raped is classed as 'high risk' probably gives you a good idea of my main criticism).

The child and family would have a number of different agencies involved in an effort to keep them safe and to reduce their risk.

The 'take responsibility' victim blaming message really takes hold here, and this is how:

"Parents need to take more responsibility for the safety of this child"

Whilst this seems fairly reasonable, because as parents, we are all legally responsible for the safety and wellbeing of our children; this is not quite what that statement means to parents of exploited children. This statement is used with parents even when they are trying absolutely everything in their power to keep their child safe but the perpetrators are just too powerful. The child climbs out of the bedroom window whilst they sleep. The perp pulls them out of school at dinner time. The perp threatens the child to ensure they run away and come back to the perp or the residence where the perpetrator are. In these situations, the power of the parents is limited. And yet, if the child continues to be exploited the child will inevitably be removed from the parents on the basis that they are failing in their responsibility to protect the child from harm. The local authority will seek to put the child in care which generally solves nothing, creates further trauma and vulnerabilities for the perp to exploit and ultimately, punishes the parents.

This is victim blaming.

Instead of focussing on the perp and the power of the perp, professionals are being taught and forced to focus on the responsibility of the parents. Rather than working with them, they eventually decide that the parenting is the source of the problem, in line with the traditional child protection model.

Even the CPS banned the criticism of the responsibility of parents in CSE cases in court - but it still happens regularly in frontline practice. The shift in language from 'blame' to 'responsibility' has meant that parents continue to be blamed, but in a more subtle manner.

The 'take responsibility' message to parents results in parents and carers feeling helpless, disengaged and blamed by professionals who are using standards of 'responsibility' unfairly against parents who cannot override the power of the perpetrator. Nor can the professionals, and yet there is no punishment or blame for that. It is common in this country to see children who are removed from parents under the explanation that they were failing to protect their children from external perpetrators of sexual abuse and exploitation - but then the children are put in care homes and foster placements who also struggle to protect them and in most cases, the risk actually increases.

Yet there is no such equivalent process for the professionals who are now also failing to protect the child. Surely, when the child is removed from the parents and the CSE continues to worsen, isn't that just evidence that the risk was never coming from the parenting or the lack of 'responsibility' of the parents themselves? Is it so hard to see that the risk comes from the perpetrators?

"We need to help the child to make better decisions and to reduce their own risk"

Nope, the children are not safe from the 'take responsibility for your own abuse' message either.

The child in this case study would be told to complete work on 'staying safe online', 'drug and alcohol awareness' and 'healthy and unhealthy relationships' - in an attempt to engage the child in taking responsibility for their own safety and ultimately, for the actions of their perpetrators. The thought process behind this baffles me.

We have a child in serious trauma, being sexually exploited, going missing and already deeply groomed by the perpetrators and the national response to that is to help the children take more responsibility for their own safety?

That horse has bolted, my friends.

Why are we even doing these pieces of work whilst they are in active exploitation and active complex trauma/crisis? We have perpetrators sexually abusing children and we get them to sit down and watch a DVD about sexting and tell them that they need to take more responsibility for their online behaviours - completely ignoring the actions and grooming methods of the perpetrator, whom is the true catalyst behind these risks.

We can do all the 'take responsibility' work we like, but if the perp is still in the picture, we are actively and consistently perpetuating victim blaming by focussing on the responsibility of a child rather than putting all of our resources into the disruption of the perpetrator.

Which brings my to my final point. You will notice that throughout this post, there has been no mention by the anti-rape wear companies, the police, the home office, the NHS or the professionals about the responsibility and decision making of the perpetrator.

I get the distinct feeling that professionals and larger structures feel that it is just too hard to target perpetrators so they target victims.

This in itself, could be construed as victim blaming.

Moving to the 'take responsibility for your own safety' message might look more socially desirable than victim blaming and it might cost organisations less money than chasing perps but this approach will not reduce sexual violence and it will not empower people who have experienced rape and sexual assault. The focus MUST shift back to the perpetrator and their responsibility.

Rather than 'don't get raped' messages, we need 'don't rape' messages.

Take responsibility

= blaming the victim.

For more information about this article or my research, get in touch.

To read the paper I wrote on this topic, click here: Portrayals and Prevention Campaigns Sexual Violence in the Media - ©VictimFocus.pdf

Get more trauma-informed content!